Echo Chambers of the Mind

- Phil Harris

- May 9, 2018

- 2 min read

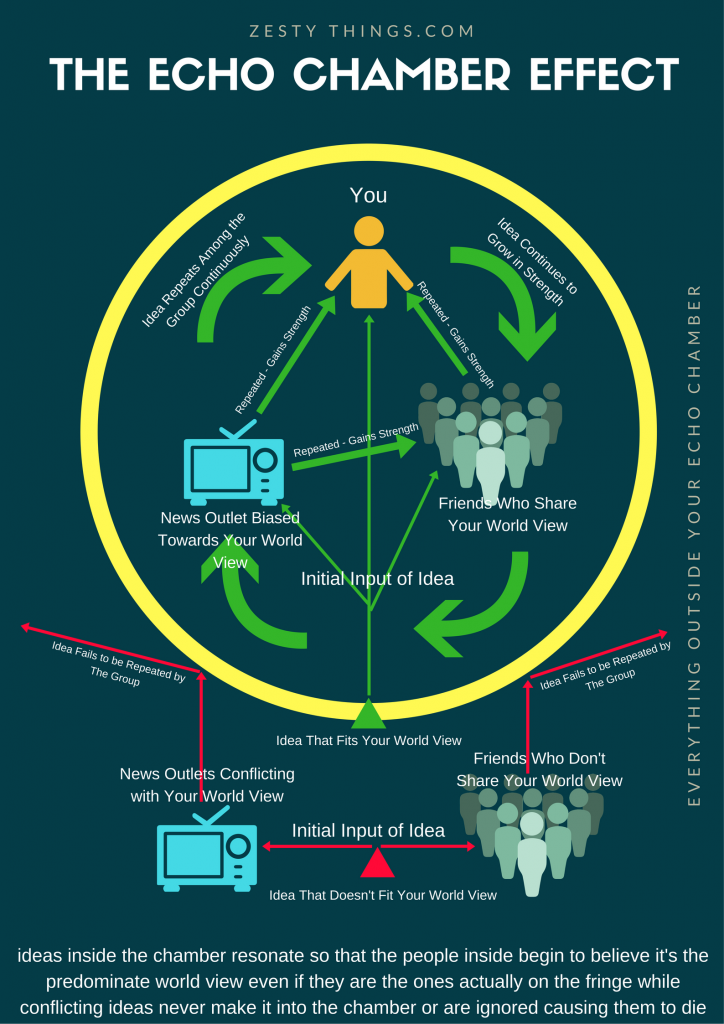

I often explore challenging research findings that questions some core assumptions about human development and treatment processes. I myself am challenged by these research findings on first discovery and have to reappraise my own thinking before being able to share it with others and develop its content for treatment design. Sharing these findings, I often get a wide range of responses from mostly fascinated interest to the occasional complete disavowal. Sometimes working in the field of it feels as though a desire to protect cherished beliefs play a much bigger role in our willingness to evaluate human nature than science. But the first question in psychology should always be why do I believe the things that I do?

This is important as we assume at times that data and well conducted research, statistics should be compelling. However, people respond emotionally to data in the first instance. If I offer data that supports people world view it is often accepted at face value. But if I share data that questions someones world view, then the research is always questioned. A recent research found that this is almost like a reflex in people.

A new study illuminates how rapid, involuntary mental processes kick in when responding to statements that correspond with an already held viewpoint, according to a study by researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The research, published in Social Psychological and Personality Science, shows how people's tendency to remain entrenched in their worldviews is supported by their automatic cognitive "reflexes."

The team led by Dr. Michael Gilead, head of the Social Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory at BGU, found that study participants verified the grammatical accuracy of statements about political topics, personal tastes and social issues much more quickly when they matched their opinion.

In a series of experiments, the researchers asked participants to respond to various opinion statements, such as "The internet has made people more isolated" or "The internet has made people more sociable," and indicate as quickly as possible if the grammar of the sentence was correct or not. Later, they were asked if they agreed with each statement. Participants identified statements to be grammatically correct more quickly when they agreed with them, which revealed a rapid, involuntary effect of agreement on cognitive processing.

According to Dr. Gilead, "In order to make informed decisions, people need to be able to consider the merits and weaknesses of different opinions and adapt to new information. This involuntary, 'reflex-like' tendency to consider things we already believe in as being true, might dampen our ability to think things through in a rational way. Future studies could explore how other factors, such as acute stress or liberal or conservative viewpoints, affect this tendency to accept or reject opinions in a 'knee-jerk' manner."

Story Source:

Materials provided by American Associates, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

Michael Gilead, Moran Sela, Anat Maril. That’s My Truth: Evidence for Involuntary Opinion Confirmation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2018; 194855061876230 DOI: 10.1177/1948550618762300

Comments